Introduction

On August 31, 2021 President Biden announced the U.S. military had withdrawn from Afghanistan, ending America’s twenty-year involvement in the country. Over 120,000 individuals, including U.S. citizens, citizens of U.S. allies, and others were airlifted out of Afghanistan, including more than 70,000 Afghan allies of the U.S. This population includes Special Immigrant Visa (SIV)-eligible individuals, their family members, and other Afghans who aided U.S. and allied forces and entities, as well as those who would qualify for refugee status.

Most of these individuals have been or will be admitted to the U.S. under parole, a process that affords temporary lawful presence in the United States for “urgent humanitarian reasons.” Individuals who enter the U.S under parole are usually granted parole for one year, but the U.S. government has announced that Afghans granted parole will be able to stay for two years. Parole does not provide any of the federal services associated with refugee resettlement, or the right to apply for lawful permanent resident (LPR) status, but does permit recipients to apply for work authorization. On September 30, 2021 Congress provided this group with access to benefits given to refugees and SIV holders via a bipartisan spending bill. However, for this group of Afghan allies, the lack of permanent legal status remains, leading to uncertainty and even potentially leading to removal from the U.S. However, Congress can provide certainty to Afghan evacuees – granting them a pathway to permanent legal status by passing an Afghan Adjustment Act.

Congress has passed similar legislation at the conclusion of several U.S.-involved conflicts or humanitarian crises in the past. Three noteworthy examples occurred following Fidel Castro’s rise to power in Cuba, after America’s withdrawal from Vietnam, and following both U.S. military actions in Iraq – Operation Desert Storm and Operation Iraqi Freedom. After these conflicts, Congress passed via legislation adjustment acts that granted Cubans, people from Southeast Asia, and Iraqis who had entered the U.S. as a non-immigrants or parolees the opportunity to adjust to LPR status. This paper will provide background on these prior adjustments, and what this means for the ongoing Afghan resettlement effort.

The Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966

Following Fidel Castro’s rise to power in Cuba in 1959, hundreds of thousands of Cubans fled the island for safe refuge in the United States. More than one million Cubans entered the U.S. via parole in 1960 and 1961, but there was no pathway at the time that would allow them to adjust to lawful permanent resident status. Following the failed U.S. invasion at the Bay of Pigs in 1961 and the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, Congress passed the Cuban Adjustment Act (CAA) of 1966 that provided a pathway to LPR status and work authorization to Cubans who had entered the U.S. after Castro came to power and continued to reside in the U.S.

To be eligible to adjust status, qualifying individuals must have been Cuban citizens or otherwise been born in Cuba, entered the U.S. on or after January 1, 1959, and resided in the U.S. for at least one year before filing their application. The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA) established that the CAA would remain in effect and continue to be in force until the president determines that a “democratically elected government in Cuba is in power.”

In addition, Cubans wishing to adjust their status under the CAA must be admissible to the U.S. However, the usual bars to adjustment do not apply to Cubans, regardless of whether they were inspected upon arrival in the U.S., or not.

The CAA differentiates between principal and dependent applicants for adjustment of status. Usually, the principal applicant, as head of the family, must submit all the necessary information for adjustment of status, including a copy of a Cuban identification document and other evidence of Cuban citizenship or Cuban birth. The principal’s spouse and minor children can also apply for an adjustment of status, although different rules apply to them. For example, dependents do not have to be Cuban citizens or have been born in Cuba. A dependent cannot adjust his or her status before the principal does, nor can he or she adjust status if the principal already has become a naturalized U.S. citizen. This restriction following the naturalization of the principal is because post-naturalization, the principle is no longer considered an “alien” under U.S. law and is thereby not covered under the CAA. If dependents themselves qualify under the CAA as principals, they would remain eligible to adjust their status regardless of whether or not the original principal had already naturalized or received LPR status through a means other than the CAA.

There have been some adjustments via executive branch actions to the CAA since its initial passage. The Migration Agreements of 1994 and 1995, which were executive actions, and not acts of Congress, created what was colloquially known as the “wet foot/dry foot” policy for Cuban migrants. Under this policy, Cubans who were intercepted at sea would be returned to Cuba, and those who made it to the U.S .would typically be granted parole and the opportunity under the CAA to adjust their status after one year of residence. However, the Obama administration in 2017 rescinded the policy, eliminating parole for Cubans escaping to the U.S. and forcing them to pass through the same immigration processes as other nationalities, except under special circumstances.

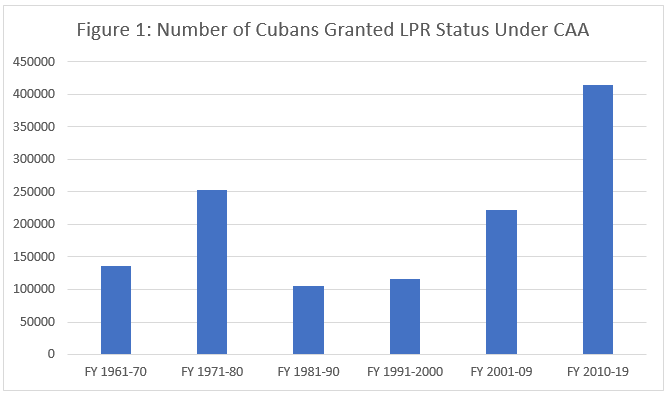

Since the passage of the CAA, over 1.2 million Cubans have obtained LPR status in the U.S. As Figure 1 demonstrates, the CAA has continuously permitted Cubans to adjust status to become LPRs over the past forty years, with the most recent decade seeing the highest number of Cubans (413,624) successfully adjusting to LPR status.

Source: DHS Yearbook of Immigration Statistics 2004-2019

Adjustment Acts Following the Vietnam War

Following the Vietnam War, Congress passed legislation to provide individuals who fled Southeast Asia a pathway to LPR status. However, unlike the CAA, post-Vietnam War adjustment was addressed by multiple pieces of legislation.

Shortly after the fall of Saigon, the Indochina Migration and Refugee Act of 1975, provided needed supplemental funding of $405 million dedicated for the resettlement of Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian, and Hmong refugees. Like the recent passage of supplemental Afghan resettlement funding, this bill did not provide an expedited pathway for adjustment. Around 135,000 refugees were admitted to the U.S., mostly through parole. Most of this first wave of refugees were highly educated and skilled, and feared reprisals for their close connections with the U.S. They were first airlifted to U.S. military bases in the Pacific – Wake Island, the Philippines, and Guam – and then transferred to refugee centers located at military bases in California, Arkansas, Florida, and Pennsylvania. The Southeast Asian migrants underwent cultural assimilation education, which included English language instruction, for multiple months. The refugees would receive federal economic support upon completion of these courses and the start of their new lives in the U.S.

The second bill, H.R. 7769, which passed in 1977, amended the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act of 1975 to provide an expedited pathway for adjustment. The bill allowed previously evacuated Southeast Asian refugees present in the U.S. to adjust their parole status to LPR status. Refugees had to have been paroled into the U.S. after March 31, 1975, but before January 1, 1979, be physically present in the U.S. for at least two years and be admissible. H.R. 7769 also provided these refugees with social services, medical assistance, cash assistance, education access, and resettlement assistance. According to DHS data, 137,309 refugees were granted LPR status under H.R. 7769 between 1971-1980, with 37,752 more obtaining LPR status between 1981-1990.

Finally, in 2000, Congress passed the Indochinese Parole Adjustment Act, which was included in the Foreign Operations Appropriations Act of 2001. The Indochinese Parole Adjustment Act allowed additional Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Laotian migrants to adjust to LPR status. To be eligible, they must have been admissible to the U.S., have been physically present in the U.S. before October 1, 1997, and paroled into the U.S. via either the Orderly Departure Program, a refugee camp in East Asia, or a UNHCR-administered camp for displaced persons in Thailand. Work authorization was also available for these individuals. The legislation provided for a maximum of 5,000 migrants adjusting to LPR status under the program.

Iraqi Adjustment

Congress acted multiple times to provide for the adjustment of Iraqi nationals following U.S. military interventions in the region. Following Operation Desert Storm (1991), Congress utilized the FY 1999 Omnibus Appropriations Act to create a pathway for Iraqi asylum seekers, mostly evacuated Kurds, to attain LPR status if they met certain prerequisites. Under Section 128 of that bill, Iraqi nationals who were U.S. government employees, employees of U.S.-based NGOs, or were evacuated to Guam by the U.S. government in 1996 or 1997, and who had asylum applications processed on Guam between September 1, 1996 and April 30, 1997, would be eligible to adjust to LPR status. The timeline and requirements set out in the appropriations provisions applied to both principals and dependents. In FY 1999, 313 Iraqis were granted LPR status and by FY 2001, 4,206 Iraqis attained LPR status. In subsequent years, according to the federal government data, the number of additional adjustments under that enactment have been extremely low – less than 50 in total.

The appropriations provision was enacted following Operation Pacific Haven (1996), in which more than 6,500 Iraqis, mostly Kurds, were evacuated by the U.S. military to Guam to protect them from threats against their safety by Saddam Hussein’s government. These individuals first crossed the border into Turkey where an initial security screening was conducted. They were then flown to Andersen Air Force Base in Guam where the asylum process would take place. On Guam, these individuals would have their asylum applications processed (which on average took between 90 to 120 days), participate in English language classes, and even learn how to operate Western appliances and amenities, such as drying machines and fire alarms. Once their visas to the U.S. were approved, many religious organizations and family members volunteered to act as sponsors. In total, the operation in Guam cost around $10 million, and was seen as highly successful.

Following Operation Iraqi Freedom (2003-11), Congress included an expedited pathway to LPR status for Iraqis in the U.S. who had served with U.S. forces or other government entities in the National Defense Authorization Act of 2008 (NDAA). Section 1244 of the 2008 NDAA provided protections to Iraqis who had provided at least one year of service to the U.S. government between March 20, 2003 and September 30, 2013, including providing assistance to the U.S. military, serving as U.S. embassy personnel, or working in other qualifying capacities, and feared for their safety as a result of their service. Under that provision, qualifying Iraqi nationals outside the U.S. were eligible to receive SIVs , and were eligible to adjust to LPR status if already in the U.S. This legislation provided for 5,000 visas annually from FY 2008 to FY 2012 and possible work authorization. Subsequent related legislation extended the program until the end of 2013, and provided 2,500 additional visas to be issued in 2014 or later. The program has not been expanded or extended since.

To be eligible to adjust to LPR status under this provision, qualifying Iraqi nationals already in the U.S. must have been paroled or admitted as a non-immigrants, be physically present in the U.S., and be admissible to the U.S. Additionally, those who applied for adjustment of status after January 1, 2014 must attach to their application a positive recommendation from a former U.S. supervisor in Iraq.

Conclusion

The U.S. has a long and successful history of creating expedited pathways to citizenship for those who aided U.S. forces in military conflicts and other situations. Following upheaval and/or U.S. military actions, the U.S. has a history of providing humanitarian support to those impacted and providing those allies with expedited pathways to adjust to LPR status and eventual citizenship.

With tens of thousands of Afghan evacuees already in the U.S. and more arriving in the coming months, it is vital that Congress immediately introduce and pass an Afghan Adjustment Act so that these individuals do not face uncertain futures in the U.S. Instead, Congress should ensure that they are given an opportunity to obtain permanent status and the stability that accompanies that status.

The alternative, forcing them to fend for themselves in the already overburdened and backlogged asylum system, would only further exacerbate backlogs and delays in the asylum system while creating additional uncertainty for this population. Urgent congressional action is necessary to provide our Afghan allies and friends a smooth transition to America and their full integration into their new lives.

*Special thanks to Joshua Rodriguez for his work on this explainer.